How Can You Build on Such a Quicksand? George Rochberg spent his life arguing for a renewal of humanist values in art. He felt the aleatoric and serial music that dominated his time was destined to …

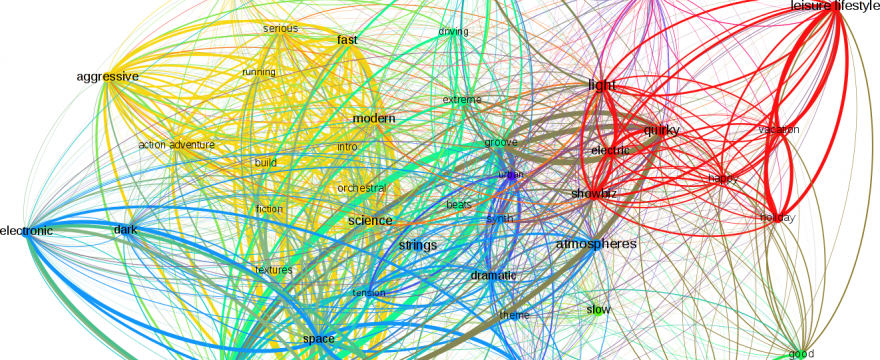

Automating Musical Descriptions: A Case Study

It's widely accepted that music elicits similar emotional responses from culturally connected groups of human listeners. Less clear is how various aspects of musical language contribute to these …

Continue Reading about Automating Musical Descriptions: A Case Study →

A Study in Stylometry

In July of 2013, Patrick Juola, a computer science/mathematics researcher at Duquesne University, uncovered the fact that J.K. Rowling was writing detective novels under an assumed name. Juola used …

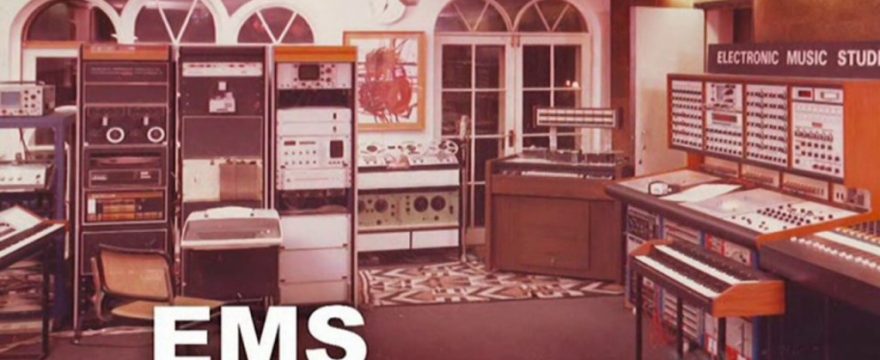

What the Future Sounds Like

Electronic music pioneer Peter Zinovieff sums up Isomer's raison d'etre in a single sentence... https://youtu.be/8KkW8Ul7Q1I?t=25m35s See this fantastic documentary in its entirety here. …

Inferring Meaning from Expectation

Of all the sublime moments in operatic literature, few surpass "Pur ti miro, pur ti godo" (I gaze at you, I possess you), the final love duet between Nero and Poppea in Monteverdi's "L'incoronazione …

Melodic Expectation: A Case Study

Due to inherent limitations in our own perceptive and cognitive abilities, we find the anticipation and realization of unexpected events and connections (within certain parameters) extremely …