How Can You Build on Such a Quicksand?

George Rochberg spent his life arguing for a renewal of humanist values in art. He felt the aleatoric and serial music that dominated his time was destined to fail the most basic test for inclusion in the ever-expanding legacy of culture — that musical experiences must be meaningful to people.

George watched as many of the musicians around him turned their backs on the values of identity and meaning in their art. Without identity and memory, there could be no meaning. Without the possibility for meaning, art would fail to exist as a holistic and satisfying experience.

For George, these elements were the very substance of life, and therefore music.

We literally must impose an order of some kind on our affective memory if we are to see meaning in our existence. It is in the power of forming the data of our existence that we shape ourselves and the world around us; and it is out of this power, this urge to meaning through form and order, that art arises.

— George Rochberg

In other words, cultivating a sense of musical identity requires the listener to recall the idea in memory and recalling musical ideas requires an adherence to culturally acquired patterns and structures. If musical elements exist without an identity (what is it? and later, what was it?), they will, at best, only offer fleeting moments of disassociated sensations. In George’s mind, music like this has “foredoomed itself to extinction”. It will never have the chance to become part of heritable culture.

The Search for Firmer Ground

Rochberg insisted that in order to escape the quicksand of musical entropy, identity and memory must operate in two places at once: at the motivic level and formally. In both cases, he suggested that a perceivable identity must be consistently present through repetition, variation, and recall. Further, he imagined that even though they all approached music very differently, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart, and Wagner would all have recognized and fully embraced these high-level concepts.

In fact, there is a growing body of research that supports this.

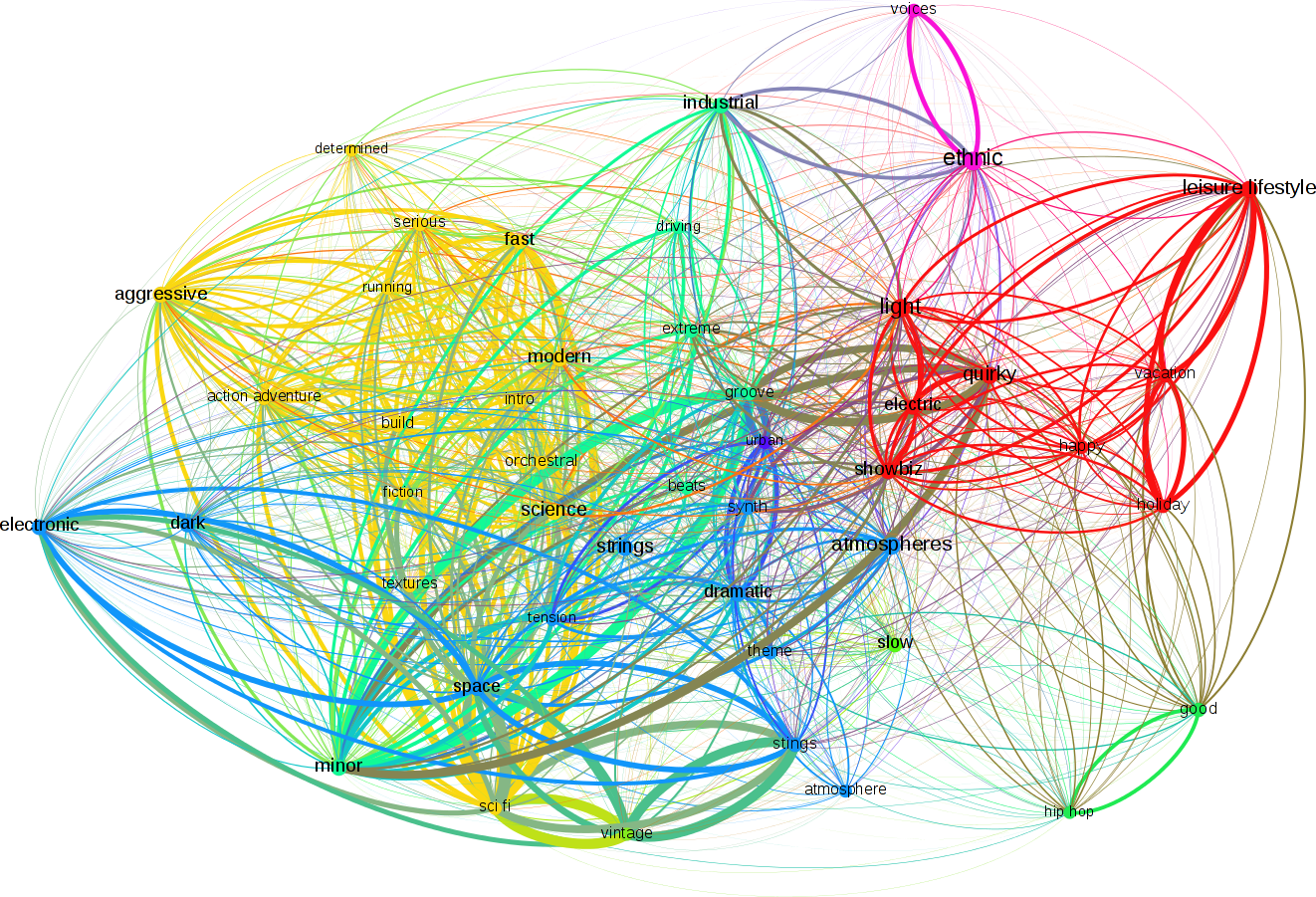

Starting in the 1950s Meyer, Younblood, Krahenbuehl, and Coons introduced serious studies involving the concepts of musical arousal, uncertainty, and surprise using principles borrowed from information theory. Since then, generative theories (Lerdahl, Jackendoff, and Narmour) and quantitative models (Huron, Margulis, and Farbood) of musical expectation and tension have shown that humans apply learned memory encoding to the sounds and musical patterns that we experience.

So, in order to find meaning in musical expression, we require structure and a perceptual adherence to culturally learned schematic patterns, structures, and devices. It seems George was on to something…

To play with entropy in art is to play with a self-consuming fire.

— George Rochberg

Self-perpetuating musical elements must incorporate the past, present, and suggest a possible future. Without this, music (pitch, harmony, duration, and ultimately, form) cannot convey movement or meaning. Without this, the questions so fundamental to human expression and existence suddenly have no answers. Where are we going? Have we arrived? Why have we arrived here?

The Problem with Allegory

While it’s clear we’ve made great strides in understanding the fundamentals of musical comprehension since the 1950s, most of this progress has yet to filter down into the lexicon of applied music. Without awareness of these discoveries, the people discussing, creating, teaching, promoting, and financing artwork remain locked in a haze of anecdotal notions when trying to assess aesthetic value, consider solutions to artistic problems, and communicate artistic ideas.

At best, we can only come away with an allegorical sense of the issues we’re attempting to address.

When talking and writing about the creative process, Rochberg often used intentionally vague phrases to convey concepts such as, “emerging on a new plane”, “transcendent qualities”, “cosmic consciousness”, “powerful connections”, and “growing an atmosphere”. He spoke of musical gestures in terms of their weight (gravity) and temperature. He even assigned these attributes to individual composers; Beethoven was “hot” while Debussy was “cold” etc.

George was far from alone in defining music in largely allegorical terms. In fact, it’s quite common to hear artistic values discussed in poetic, ephemeral, mystical, or even supernatural terms. Of course metaphysical descriptions of music are useful because they convey more than the words themselves might imply. Thinking about art in this way can inspire an artist to imagine beyond the obvious solutions that present themselves and discover novel, more satisfying results.

But it’s not without a significant downside.

Relying on allegory when discussing the complexities of artistic expression can introduce unnecessary confusion, stunt communication, and hinder artistic progress. Ignoring (or hiding from) the tangibles surrounding the artistic process imposes an emotionally-biased and highly-subjective system of judgment that is difficult to apply in practical terms. Most importantly, it closes the door on ideas that exist outside of the internally-defined borders of acceptance, often without reason or evidence.

German poet and critic, Hans Magnus Enzensberger saw this problem and described it nicely:

The moment a topological structure appears as a metaphysical structure the game loses its dialectical balance, and literature turns into a means of demonstrating that the world is essentially impenetrable, that any communication is impossible. The labyrinth thus ceases to be a challenge to human intelligence and establishes itself as a facsimile of the world and of society.

Pragmatic and Progressively Human

Allegorical representations of musical expression have value, but the creation of art is also concerned with definable practicalities. Like Enzensberger and others, I see a balanced approach as essential to progress. As such, I am interested in (and even inspired by) the inevitable march of technological progress and the influence it is exerting on the future of art. Moreover, I find that the inclusion of an information-driven perspective offers a convincing theoretical model of our own human creative processes.

My work in music (as composer, pianist, and researcher) has been focused on developing a practical, useful, and tangible understanding of these principles — in order to ensure the survival of music as a progressively human expression of art.

George (and others) rejected the reduction of musical information to parameters upon which a person can operate. Perhaps more importantly, he worried about the result of imposing a strictly rational order on this data to create new art — an order that might not take into account his concerns with memory and identity.

My claim is that many of the artistic values that we as artists hold dear are present in the discrete parameters of music. This includes memory, identity, and even an understanding of expressive qualities of musical character. Further, algorithms are no longer limited to the simplistic and prescriptive ordering of musical data. Today we can create software that is flexible, adaptive, and if trained against representative human examples, is even able to contribute meaningful expressions of art.