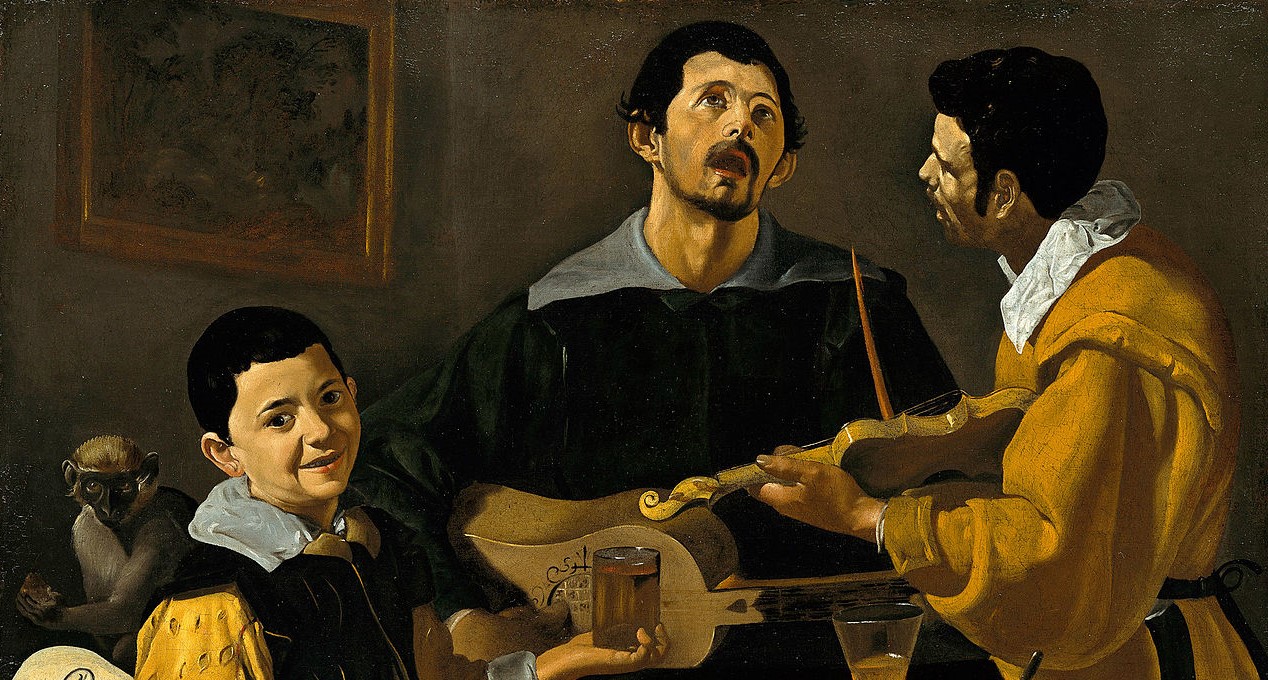

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age. In particular, his uncanny ability to capture the lens-accurate effects of light and shadow in intricate and provocatively staged scenes has elevated him to the status of revolutionary master.

There’s something very special there. Almost spiritual. And yet, we can’t quite put our finger on it.

— Tracy Chevalier, Historical Novelist on Vermeer

Recently, inventor Tim Jenison spent more than five years developing and testing theories around the possibility that Vermeer relied heavily on machines to produce the 36 masterworks attributed to him today. While it’s unclear how applicable Jenison’s results are to Vermeer’s actual process, the backlash from his efforts makes it clear that associating influential artwork to a partially mechanical process is a decidedly unpopular thing to do.

Should Technology Play a Creative Role?

Of course, art is never created in a technological vacuum. Advances in paint pigmentation, musical instrument construction, and so on, are examples of technology’s direct influence on artistic output. And yet many cry foul when they suspect a technology may be brushing up against the essence of an artwork.

When confronted with art that acknowledges direct technological involvement in the creative process, people often say they feel deprived of an authentic artistic experience. They feel cheated in some way.

I’ve experienced this bias from non-musicians and professional musicians, and I’m not alone. While I understand why people might draw similar battlelines in other aspects of their lives (e.g. politics and spirituality), I’m left frustrated and confused when it comes to the role of technology in art. How can the source of the artifact count for more than the artistic value of the work itself?

Perhaps a little armchair theorizing will help me understand — or at least feel better about — the apparent state of things.

Touchable Technologies

Could it be that certain technologies are more readily accepted because they appear to be within the immediate control of the artists themselves? For example, while most composers would be unable to fashion a working clarinet from raw materials, it’s certain that most have worked closely with numerous clarinets and clarinetists, so as to understand the limitations and advantages of the physical mechanisms employed.

Could it be that certain technologies are more readily accepted because they appear to be within the immediate control of the artists themselves? For example, while most composers would be unable to fashion a working clarinet from raw materials, it’s certain that most have worked closely with numerous clarinets and clarinetists, so as to understand the limitations and advantages of the physical mechanisms employed.

Is a composer’s use of “clarinet technology” acceptable because we can touch it? Are clarinets welcome because they’ve been around (in one form or another) for hundreds of years? Does the mechanical nature of physical instruments and tools seem more grounded to us?

This sounds plausible.

Untouchable Technologies

But if touchability is so important, why then is it acceptable to use software to design and/or implement an artistic idea?

Most often, creators employ digital tools as a series of black boxes with very little knowledge of their internal workings. Artists using these tools can be unwittingly influenced (or even held hostage) by interfaces, opcodes, and algorithms they didn’t create.

And yet, artists using technologies like these are rarely (if ever) seen as engaging in artistic trickery or cheating, nor do they feel these tools are outside of their control.

Strike.

Maybe it’s time to turn the question of artistic authenticity on its head. What can we learn by examining other examples of artistic practice that are commonly viewed as deceptive?

The (Dis)Advantage of Influence

Just as certain applications of technology appear to influence the assumed integrity of a given artwork, the same may be said for the amount and type of perceived influence any given work contains.

I say “perceived” because it is often the case that deep influence between artists and composers go misappropriated or even unnoticed. In fact, the attribution of landmark innovations can be so widely mistaken that the error becomes an indelible part of the canon.

Even so, the questions that arise are familiar…

- When artists draw heavily from existing artwork (whatever their intent), is it a form of cheating?

- Where should lines be drawn between artistic influence, parody and copying?

- Is it acceptable for artists to copy (or borrow) from themselves?

- When is artistic appropriation a creative act, and when does it devolve into plagiarism?

This feels closely related to questions surrounding our Vermeer example such as: when does a mechanically-aided artistic process cease to be a creative act?

Hrm…

Maybe what upsets people isn’t the use of technology per se, but rather a perceived loss of artistic authenticity and uniqueness. Adding to the confusion, perceived signals of artistic authenticity are in a constant state of flux…

A Modern View

Interpreting evidence that Vermeer was an extremely clever engineer with a talent for theatrical staging (who happened to produce incredibly important and influential artworks) is offensive to many — at least today. I suspect the same would be true if evidence surfaced suggesting that Bach’s ingenious counterpoint was significantly made possible by an incredibly clever (but long forgotten) 17th century machine.

Interpreting evidence that Vermeer was an extremely clever engineer with a talent for theatrical staging (who happened to produce incredibly important and influential artworks) is offensive to many — at least today. I suspect the same would be true if evidence surfaced suggesting that Bach’s ingenious counterpoint was significantly made possible by an incredibly clever (but long forgotten) 17th century machine.

It’s important to remember that these illustrations carry the full force of history behind them. A distant history whereby it’s impossible to know with certainty how any specific artwork was created. Of course, this isn’t true for new pieces created by machines. But this fact only makes it that much easier for people to dismiss machine-generated music as less worthy of repetition — especially in an time of A.I. buzzword fatigue and algorithmic intrusion into our daily lives.

Parting Thoughts

I recently had the opportunity to see several of Vermeer’s paintings with my own eyes. Great googily moogily. The light in these paintings are unlike anything else I’ve seen.

I’m certainly no expert, but the illumination sure feels lens-accurate to me. And so what if it is? The paintings are so much more than the unprecedented technical execution of light and shadow. So much more…

The truth is — I have yet to hear music produced by a machine that rises to the quality of what humans create. But don’t mistake this for pessimism. There are many worthwhile efforts underway. We’re just getting started. And unlike some, I welcome our new algorithmic overlords.