or… “How Others Did It So Much Better”

The following is a video script I prepared, but never filmed. In the end, I decided I had better things to do, but perhaps the idea is of interest?

VIDEO: Me playing the Drowning Church

VOICE OVER

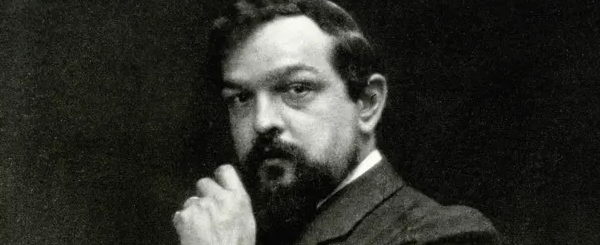

When I first encountered Debussy, it was here. With this piece.

At the time, my hands weren’t yet big enough to reach the wide spreads… and strange shapes… but that’s not why I found it difficult. It was difficult because I couldn’t find a way to convincingly express anything musical.

It was like the composer needed to convince himself that gravity didn’t apply to him – in my hands, the music couldn’t escape a suffocating heaviness… everything… just… went nowhere…

Debussy was not for me.

VIDEO: Greg speaks directly to the camera while music continues in the background

Of course, Debussy’s influence then and now is undeniable. But I’m still not convinced. And 40 years later, I think I know why…

CHANNEL SPLASH

VIDEO: Greg speaks to camera

TEXT OVERLAY: “Debussy Oversimplified”

Debussy’s legacy and influence comes down to a couple of things:

- he rejected common practice counterpoint and voice leading

- relied on parallel harmony that broke formal conventions

- and most important – the sound texture mattered above all else (symbolism)

VIDEO: composer headshots of Ravel, Satie, Scriabin…

BUT the thing is… other composers around that time were making similar choices – advancing musical language – and they were writing better music.

VIDEO: New Location – Greg Speaks to camera

Musical events are connected in time by our brains – this an unavoidable principle of musical language. One event next to another – implies a range of NEXT options… and if we go too far outside what was implied… the connection can be lost.

Ignoring this is like deciding to ignore physics just so you can build a perpetual motion machine.

Let me show you what I mean.

VIDEO: Me playing Moons Over My Hammy

TEXT OVERLAY: “Sweet Anticipation”

VOICE OVER

Let’s take the opening of one of Debussy’s most famous works – Clair de Lune.

If at any moment…

ANYTHING can happen…

The connection is lost. The implication isn’t strong enough to imply a satisfying resolution.

A sense of anticipation is never created – because just about anything… can happen… and all we can do is take it in.

Anticipation requires that we look forward to something… and THAT depends on what we JUST heard.

VIDEO: New Location – Greg Speaks to camera

If you know this piece, you realize that I just started adding random bits of… whatever. If you don’t know this piece, you probably weren’t bothered.

Now… creating a sense of suspended animation – of floating aimlessly in a hazy mist – can be done in so many wonderfully compelling ways – ways that maintain and deepen connections to the way our brains listen – and ways that still feel as “magical” as anything you can dream up…

VIDEO: Me playing Gymnopédie No. 1

TEXT OVERLAY: “Suspended Animation Doesn’t Exists Without Movement”

VOICE OVER

Here the composer sets up several expectations…

A “looping” accompaniment of sorts…

And a beautiful melody that has clear direction…

Even if it takes some time to complete…

This is Erik Satie. He wrote this in 1888 and in many ways, this is the earliest “ambient” music.

But it creates a sense of stillness through the illusion of suspended animation. Expectations are set forth and satisfied on multiple levels and we don’t have to ignore the way our brains embrace music!

VIDEO: Me playing Scriabin Op. 74

TEXT OVERLAY: “To Break Rules, You Must First Know The Rules”

VOICE OVER

In this case, Alexander Sciabin has discarded traditional harmony in favor of symmetrical harmonic structures. He’s breakin’ the rules. (what a rebel!)

But a sense of anticipation with a relatively limited set of options is maintained.

And yet we’re absolutely floating in a fragrant cloud of misty goodness – gravity is intact. And the anticipation is sweet.

VIDEO: New Location – Greg Speaks to camera

So there it is.

40 years after I struggled to give this music direction…

I learned that it doesn’t have any. At least not to my ears…

VIDEO: Me playing the Drowning Church

VOICE OVER

I’d like to know what you think about Debussy and my take… Leave your thoughts in the comments below. I look forward to you showing me the error of my ways!

Could it be that certain technologies are more readily accepted because they appear to be within the immediate control of the artists themselves? For example, while most composers would be unable to fashion a working clarinet from raw materials, it’s certain that most have worked closely with numerous clarinets and clarinetists, so as to understand the limitations and advantages of the physical mechanisms employed.

Could it be that certain technologies are more readily accepted because they appear to be within the immediate control of the artists themselves? For example, while most composers would be unable to fashion a working clarinet from raw materials, it’s certain that most have worked closely with numerous clarinets and clarinetists, so as to understand the limitations and advantages of the physical mechanisms employed.

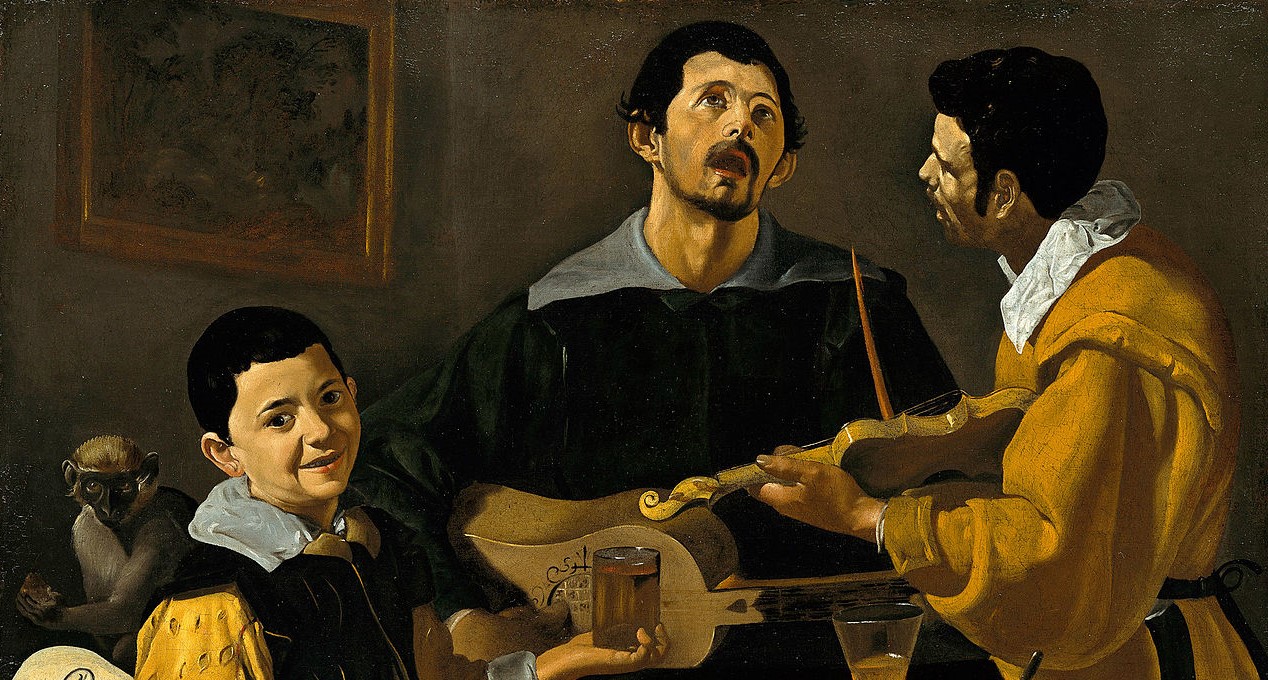

Interpreting evidence that Vermeer was an extremely clever engineer with a talent for theatrical staging (who happened to produce incredibly important and influential artworks) is offensive to many — at least today. I suspect the same would be true if evidence surfaced suggesting that Bach’s ingenious counterpoint was significantly made possible by an incredibly clever (but long forgotten) 17th century machine.

Interpreting evidence that Vermeer was an extremely clever engineer with a talent for theatrical staging (who happened to produce incredibly important and influential artworks) is offensive to many — at least today. I suspect the same would be true if evidence surfaced suggesting that Bach’s ingenious counterpoint was significantly made possible by an incredibly clever (but long forgotten) 17th century machine.