or... "How Others Did It So Much Better" The following is a video script I prepared, but never filmed. In the end, I decided I had better things to do, but perhaps the idea is of …

What To Know Before Mixing In Dolby Atmos

Dolby Atmos is here and it's tempting to route a few audio tracks into your multichannel bus and invite your family and friends for a festival of frenetic panning. But in reality, it's tough to create …

Continue Reading about What To Know Before Mixing In Dolby Atmos →

2 Channels Deep

Last March I reconfigured the studio to accommodate a wide 4 channel stereo speaker setup. I began developing several projects for this front-facing semi-circle, but found they translated horribly …

Towards a Progressive Art

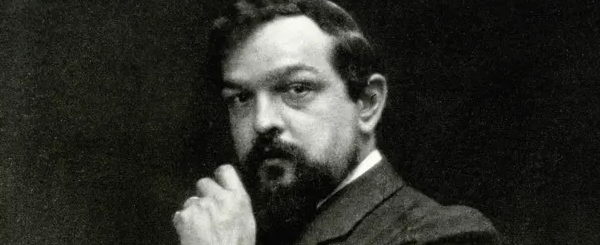

How Can You Build on Such a Quicksand? George Rochberg spent his life arguing for a renewal of humanist values in art. He felt the aleatoric and serial music that dominated his time was destined to …

The Aural Savant

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest painters of the Dutch Golden Age. In particular, his uncanny ability to capture the lens-accurate effects of light and shadow …

Allan Schindler Memorial

Allan Schindler, my friend, mentor, and colleague, passed away suddenly on October 8th, 2018. The folks at Eastman reached out to colleagues and alumni, and set up a memorial concert for Allan on …